What factors do you need to consider to build an amazing soybean factory? Todd Steinacher presents Dustin Bowling, the AgriGold Western Agronomy Manager. In this episode, Dustin compares soybeans to a factory. Soybeans are amazing plants, but they’re not as simple as you think. Today’s yielding conditions prove many factors go into ensuring maximum soybean growth. To understand how a soybean grows throughout the season, you have to understand a bit of the internal processes of a soybean plant and how it works. Join in the conversation to know more about the internal processes of a soybean plant. You wouldn’t want to miss this episode. Tune in!

—

Listen to the podcast here:

A Look Inside The Amazing Soybean Factory With Dustin Bowling, Western Agronomy Manager

In this episode, I’d like to take a deeper dive into the amazing plant that is soybeans or the soybean factory. With that, I would like to introduce our returning guest, AgriGold Western Agronomy Manager Dustin Bowling.

—

Dustin, welcome back to the show.

Thanks a lot, Todd.

It’s been several months since we chatted about different things going out in the fields, but now that harvest is upon us. Specifically, from a soybean standpoint, what are you seeing out in the countryside?

The territory that I’ve mostly been traveling in here is West of the Mississippi, Missouri, Kansas, up into the Dakotas into Western Minnesota. It’s the territory that I cover and work with AgriGold and all the agronomy teams through those states. The soybean yields are coming very strong. We’ve seen a lot more harvest activity in the I-80 corridor, those late group 1, early group 2, maybe even into the early group 3. Right now, that zone looks like not only they’re going to have fantastic corn yields, they’re going to have excellent soybean yields as well. It goes back to planting windows. That zone is from Kearney, Nebraska to Des Moines.

When you look at that pocket, they had a beautiful pocket for corn planting and soybean planting late April into early May where we were getting drowned out down here in Missouri and parts of Illinois. The ability to get that crop in quickly and uniform nice soils is paying off for both crops. The real big factor here is the importance of water at pod fill is huge. Many of us know, as you start to go North into Northwest Iowa, parts of the Dakotas, Western Minnesota, and in Central Minnesota as well, there are just some big dry pockets. That’s going to have a pretty big impact on the yields up there.

The yields are coming in okay besides for the very severe locations of drought. All in all, I think that I-80 corridor is going to be huge from a yield perspective from soybean. Anything that’s irrigated with good fertility, we’re seeing stuff over 100-bushels and plot averages. Not a lot of yields coming in under 70 in those places. It’s pretty exciting to see early group three stuff as you come into Missouri. We’re much later planted, but we had tremendous rainfall in July and August, which we typically don’t get. Even those June planted beans, we’re seeing some 55 to 65-bushel averages on some grounds that if it would happen to get very dry, you can get down into the low 40s really quick.

That’s definitely understandable. It seems like geographically, where you’re located, whether it be in the Western side where you’re at or even on my side, the Eastern side, this microenvironment can influence how a crop is going to withstand the season and how it comes into yield at the end of the day, and you had referenced moisture around that pod fill. Wherever rainfall hits us is where we tend to have good yields or poor yields so we can always watch the weather and gives us an indication from a performance standpoint.

You could definitely have too much moisture as the majority of Missouri, North Central Missouri, and parts of Illinois have seen 20 to 25 inches of rain in a three-week period. A little too much on this corn crop and a little too much on newly planted soybeans. That’s why we’ve got a lot of replants across the state. Late season moisture, that’s always a key that’s just tried and true.

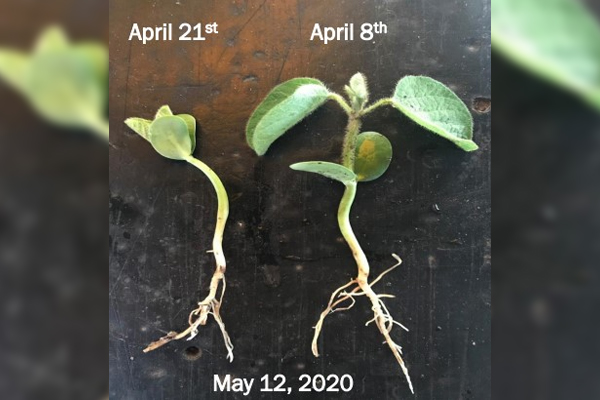

The soybean crop, very specifically soybeans, is gone through a lot of challenges in rollercoaster since planting. At least in my part of the world, there is a lot of early planting because it was maybe just a bit too cool for corn. We’re worried about the chilling impact and the root development, so there’s a lot of soybeans planted early. A lot of soybeans may have had frosting on it even though the bean crop was abused early on. Early indications of harvest I’m seeing is very promising and rewarding to some of those early-season decisions.

When you think about a soybean, we’ve always known that a soybean plant is tough. It’s very drought tolerant. It seems like we can grow it on marginal soils and still gain bushels. For the past few years, I’ve gained such huge respect for the soybean’s ability to be planted earlier and withstand colder temperatures during those early vegetative stages, to be planted and suck that warm moisture in early for the seed to imbibe that warmer water, but then to be able to withstand these massive dips of temperature that we’re seeing in April, particularly 2019 and 2020 and even again in 2021. At the end of the day, that early planting, as long as you’ve got some water at pod fill, there’s more pod counts, which equals more yield at the end of the day.

I know I was in a soybean study on the East side of the state around Bowling Green. One of our partners over there, Braungardt Ag, put out an awesome soybean planting study, which is very hard to do this 2021 with the timing of rain, but March 9th, April 15th, May 12th, June 15th and then into July 9th, 2021. I haven’t seen the yields from that study yet, but just doing pod counts, it’s clockwork. Every two weeks that you delay planting, you start to decline in pod counts by 15 to 20 pods. I can’t wait to see that study and how it turns out, but it’s a testament that the soybean plant can handle cold weather probably better than what we’ve given it credit in the past.

Before we dive into the conversation at hand as far as it relates to understanding the soybean as a factory, harvest is taking place across the large footprint of AgriGold and harvest is always the scorecard. Dustin, you being on the product development team and being that leader of products, anything associated with AgriGold soybeans, what gets you excited at first? What you’ve seen as far as the 2022 class is trying to help understand some of those complexities within the soybean lineups moving forward?

The thing I’m most excited about is just the number of options we have. We launched soybeans in 2016. For 85 years prior to that, we were only corn and we did it very well. AgriGold does corn extremely well, so we had big shoes to fill. In 2016, I had the opportunity to be a part of the team that worked to help behind the scenes and launch AgriGold Soybeans.

At that time, we had sixteen varieties and they were all Xtend and throughout the years, we’ve been building and refining that lineup. Here we are setting in 2021, our plots are full of not only Xtends. We have Legacy Xtend products that are fantastic in performance. We’ve got an entire lineup of Xtendflex, brand new soybeans with the flex trait there.

We also have E3. AgriGold is one of the very few soybean companies in the industry. As you look towards 2022, that’s going to have a trait package for literally all growers across the country. Whether you’re in one of those intense E3 pockets or maybe you’re in the Western corn belt and one of those intense Xtend usage pockets, we’ve got a bean for everyone.

The other thing that we’ve done throughout the course of our history here from 2016 is we’ve expanded just in geography that we cover with soybean. We launched our first-ever 0.3 RM as to get into the Red River Valley there in that Fargo, North Dakota pocket. We have a bean for there. We have a 5.5 maturity for the East Coast and Delta. The number of options we’ve got is amazing to see and it’s going to be fun to watch in 2022 as all this comes together.

Before coming to AgriGold, I spent most of my career in soybeans. I got to take a year off, as I call it, the sabbatical away from soybeans. Believe it or not, I missed soybeans. I’m glad that we’re diving so far into soybeans because, as markets change and acres may demand, it may be more of a rotation by us being able to offer soybeans to growers regardless of the trait platform to help with those options. We’re giving our growers more options that we can help influence some of those agronomic recommendations. It’s very exciting to be in that piece of it as well.

The growers’ need for diversity on the soybean side is huge too. We’re seeing soybean growers try a lot of different things, be it based on maturity or certain agronomic needs. We see sudden deaths moving farther North. We see white mold come South. Having more options means a better opportunity for high performance for our customers.

For the longest time, soybeans were easy. We could plant them in a relatively high population, spray them once or twice. As long as they cut good, they were pretty decent. For the last couple of years, even moving forward, that complexity just keeps building and maybe we need to start using some of these concepts we’ve worked from corn. I feel like we’ve almost had the corn mapped out of how to make it tick and improve yields.

It’s almost at a point where we need to take some of those theories and bring it over to soybeans, but then almost give it a soybean twist. That’s where I like our conversation. We’re going to go talking about the soybean factory. For the readers, Dustin and I have been chatting about this topic since 2020 and he laid the seed foundation in my head thinking about soybeans as a factory and how do we build that factory up so its output could be bushels and yields. With that, I would like you to take us down the path of talking about soybeans as a factory and how we can influence that factory.

This has been a little bit of a passion project behind the scenes for myself and thinking about those individual plants as a factory. I have a good friend that works in the industry. He works in a plant. When he comes to my house and I ask him how things are going, he’s like, “The plant is running smooth.” It just hit me. There’s a reason we call these very complex facilities plants. They are put into a specific geography. They are designed to use all of the resources from that area to produce an end product. Just like planting a seed in the ground or planting an acre of soybeans, we’re leveraging all those natural resources that are in that geography to produce an end product.

When we think about the soybean as an actual individual factory, they can help us break down not only the key timings throughout the season because we only have so much time to produce an end product, but also to take a look at just the general functioning of that factory. A wise man once told me, “Don’t be afraid to state the obvious and state the simple truth because those simple truths often have the heaviest weights.” By credit cracking the soybean down to its basic principles, I feel like there’s some learning opportunity because, as an industry, you hit the nail on the head.

We feel like we have corn figured out. We feel like we can do things with corn and do different practices, and the corn plant will react and put more bushels on. It makes us feel good as growers when we do that, then you can try the same things on a soybean plant and you end up just scratching your head. Sometimes, you’d pour a ton of inputs into a soybean plant, you might have been better off just letting it do its thing. It’s an incredibly stubborn plant, but again, as we crack down and look at this factory concept around simplifying the soybean, there are some things we can learn out of it.

I know you’ve broken down this factory into different quadrants. One being stand establishment, vegetative growth, flowering, and pod fill. If we sit back and think about the whole bean growing season, it can be very overwhelming, but I like how you break down these mini quarters. If we can have influence over each of these quarters, we can have better outcome bushels per acre or improved performance from that standpoint. In a lot of cases, what we do in quarter one is going to have a direct influence on quarter four. To me, it’s all about making the right decisions throughout the growing season.

Before we dive deep right into planting, one of the things that I should have said as I was describing the factory concept is it takes a tremendous number of resources to produce a bushel of soybean. It’s no different than the ability of a car factory to produce a bunch of cars at the end of the season. There are some very important raw materials that have to come together throughout the season and all those quarters of growing to let a soybean plant maximize its output.

Giving growers more options means better high-performance opportunities for customers.

When we talk about what raw materials have to go in to create a bushel of soybeans, we’re talking about all those macronutrients, the N, P, and K of all the secondary nutrients, the calcium, sulfur, micronutrients, boron, all those things have to be there, but we skip over the big three. A lot of times, as farmers, we skip over the biggest three macronutrients because we don’t have to walk in and actually pay for them. I’m talking about carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen.

To truly understand how a soybean grows throughout the season, we have to understand a bit about the internal processes of a soybean plant and how it works. A lot of it has to do with those three major elements. When we think about carbon, we think about oxygen and hydrogen. Carbon is the infrastructure plus a bit of energy. It is the building block of life on our planet. Everything that’s organic in this world has carbon in it. Every organic compound has a carbon to nitrogen ratio. It is truly the building block of any organic compound.

When you think about the carbon to nitrogen ratio, what does he mean there? The more carbon you have, the harder the substance is. When you think about sawdust, it has a carbon to nitrogen ratio of about 325 to 1 part nitrogen. Lush green alfalfa, on the other hand, is about 12 parts of carbon to 1 pound of nitrogen. It’s going to break down a lot easier and then you can look at a diamond. A diamond is basically the purest form of carbon on Earth. That’s why it’s a very rare gem. It’s the hardest organic compound on Earth. It’s why it’s worth a lot of money. The carbon piece of it is pretty important. When you look at those three as functioning in the factory, they’re the energy source of the factory.

They’re the two compounds that have to all come together with carbon to produce a product called glucose. When you take a six-chain molecule of carbon dioxide and combine it with a six-chain molecule of H2O, combine that with sunlight, that’s where the magic happens. Without these three major nutrients doing their thing in the soybean plant, you can have all the N, P, and K in the world. That’s where you’re going to run out of steam in order to even run the factory.

That’s important because different plants don’t handle carbon dioxide the same way. The buzzword around the industry and climate change is all about fixing carbon and there are three different plant groups that fix carbon in three different ways. When we think about carbon fixation, each plant has a metabolism If you want to simplify it down to its ability to fix carbon.

There are three different groups. There’s the C3 group of plants, which is 85% of all the plants on Earth, fixed carbon in the C3 pathway. They do this by opening up their stomates. Those are those little structures on the bottom side of the leaf that regulate the respiration of the plant. When they open up those stomates, they’re sucking CO2 in. They’re fixing carbon from the air and then they’re using that for its all of its internal processes to fix a three-chain molecule that’s used by the plant. The interesting thing about the C3 pathway is that it only operates as long as its stomates are open.

When you experience heat stress and things like that, that plant will tend to shut those stomates down in order to limit its energy expression to save its energy, but when the stomates are shut down, that plant is not actually fixing carbon internally. That leads me to our next group of plants. Those are the C4 plants. The C4 pathway of photosynthesis and carbon fixation operate the same way. They’re open up their stomates, they’re sucking CO2 in, and they are fixing a, not a three chain, but a four-chain molecule of carbon.

The C4 pathway plant can actually fix a lot more carbon on the same day as a C3 plant. These plants are often tropical in nature. They’re from areas of adaptation, have a lot of heat and a lot of humidity. A perfect example of a C4 plant is a corn plant. It’s tropical grass. We often wonder why we always see those little volunteer corn plants end up towering above our soybean plants. They can fix carbon so much faster than a soybean. It will always out-compete it. We referenced that to try and some things from corn trying to make a soybean take some of those same practices.

Internally, they’re just different. The soybean is playing the long game. It has a slower metabolism. It’s not a highly responsive plant, whereas a corn plant is extremely responsive. It’s like a sprinter. It’s going hard as fixing as much carbon as it possibly can. The practices that impact a corn plant or the inputs we try and different strategies may not always work in a soybean. Most of our growers understand that. The very last pathway of carbon fixation is the CAM pathway.

This oftentimes refers to the cacti family. It’s very arid and dry conditions. These plants fixed carbon similar to the C3, except they do it only at night. If it’s so hot and dry during the day, they keep their stomates close then at nighttime, they’re fixing the carbon they need from the atmosphere. It’s interesting when we break it down to that in-depth of a level, but at the same time, we need to understand why soybeans do what they do and why corn plant does what it does.

We think that plants are plants. We know there are grasses and there’s broadleaf but it even breaks it down to this. The cellular level and how it processes carbon and gets its energy. If in that C3, the soybean, it needs these stomates to be engaging. If we have a plant that might be under more stress, or maybe we have some fertility issues that specifically support that, our opportunities to have those stomates open might be reduced. All those management practices leading into this could help support that, correct?

You bet. To put it into better perspective on just the amount of carbon that can be fixed versus one crop to another. If you think about planting a soybean crop, we’re planting 120,000 to 140,000 seeds per acre with a soybean crop in general. At the end of the day, if we end up with 80 bushels of overall production on that acre, we feel like we did a fantastic job. Likewise, look at a corn plant and how we plant an acre of corn. We’re dropping 30,000 seeds per acre.

A fourth of the seeds we have to plant with a soybean plant and we can grow 250 bushels. We can harvest 250 bushels and fix enough carbon to get that done on one acre. It just goes to show how much more and how much more aggressive of a growth pattern and how much better corn plant is at harvesting sunlight and harvesting nutrients versus a soybean plant.

I got to ask an odd question. C4 is are fast-paced, metabolized, and they grow fast. Could I assume that certain weeds might fall into that category?

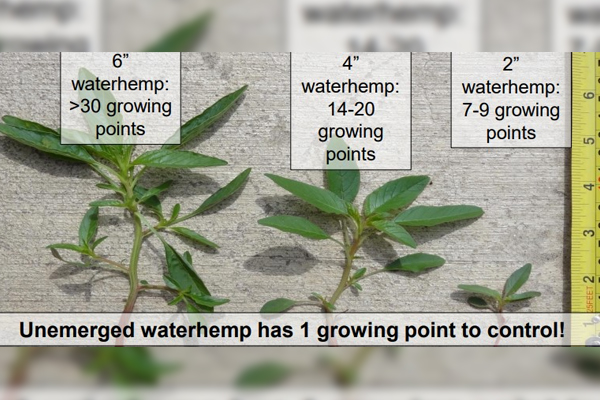

You definitely can. When we think of weed species that have adapted and come from more tropical backgrounds, we have to talk about the amaranth family. When I talk about the amaranth family of weeds, we’re talking about waterhemp and Palmer amaranth. That pesky nuisance, I jokingly call it the Missouri state flower. I feel like I’ve been battling waterhemp since my early days of working in Ag retail, coming right out of college.

The waterhemp has a very similar metabolism to a corn plant. If you want it to break it down to that simple little fashion, it can fix almost 50% more carbon in a day than a soybean plant can. We always have these growers scratch their heads about, “We end up having a bad rain event. We can’t get our fields sprayed. We go in there and the weeds are too big. We don’t put a residual down with our posts.” Growers are always so shocked to see a waterhemp plant start sticking that seed head up here about this time of year into August and September.

If you let a waterhemp plant and a soybean plant germinate at the exact same time, that waterhemp plant is going to out-compete that soybean in every instance. It is going to double or triple in size versus a soybean plant. If we don’t get our soybean plants out and get them up and growing and give them a head start, the waterhemp will catch them. We often wonder why PREs worked so good on waterhemp. Back in my early years of working in Ag retail right out of college, I came out in 2004. It was my very first season of helping farmers grow an acre of soybean or corn.

I can just think back and remember the very best soybean growers that I worked with, and this is Missouri River Bottom, highly productive, for soybean were using PREs even in a time of Roundup dominance before resistance showed its head. Some of my best growers were using Prowl. I’m thinking, “Why aren’t you using this?” I was one of those typical, hot-button terminologies of a Roundup baby. I came right into that culture. That didn’t last long because we started to develop resistance in a big way.

I ended up having to spend a lot of time in the chemical room, dusting awful jugs and reading labels and figuring out how some of these other herbicides could work. Lo and behold, those growers that were using the Prowls, using the Sulfentrazone or the Authority products real early, those early adopters, they always had fantastic soybean yields and they were always clean. It makes sense because as waterhemp has become an issue. Again, it’s got an aggressive growth habit. If you think about a waterhemp plant, when it’s emerging, it only has one growing point, which is why preemergent and residual products work so good. That seed is very small, so it has a fairly shallow depth that it will germinate.

If we can get a good layer of PREs as that seed germinates, that one growing point is highly susceptible to chemistry. On the flip side, if you let a waterhemp plant get six inches tall, it might have already 30 growing points on it. If you’re in a situation, no matter what trait package you decide to go with in 2021, whether you’re an Xtendflex grower or an Enlist user, if you’re letting waterhemp get 6, 8, 10, to 12 inches tall, both of those chemistries are going to struggle to get enough coverage to do an efficient job or control on a plant like waterhemp. If we let them get ahead, they’re not going to give up their lead to a soybean crop.

We keep seeing a lot of advocacies going around using residuals or layering residuals. Not always focusing on post-applied chemistry because we start getting more growing points, we can have issues from the systemic of a post, we’ve got issues with coverage droplet sizes. As you said, once that waterhemp emerges, it’s got one growing point. If we start getting 6 to 8 inches, we have a lot of growing points to compete with as well as a lot of soybean canopy that’s competing with from a coverage standpoint.

As we think about waterhemp, if it is aggressively growing out there, it’s competing for those same raw nutrients that you’d reference. It’s competing for sunlight and it’s just putting stress on that bean plant, so the stomates may not be working as fast as they can to build that factory. It’s so important to keep weeds in check as we’re building this factory.

It’s back to that fixing carbon thing. The plant is not only fixing carbon just for its individual growth and its individual use. It’s exchanging that. The carbon is fixing in a glucose form down through its roots its exudates and trading that with that microbiology in the soil for key nutrients. If you’ve got a plant root system that’s fixing two X the amount of carbon right next to you, who are the microbes going to go to and feed nutrition to feed the phosphorus and the nitrogen and a breakdown of organic matter. They’re going to get more carbon from the waterhemp plant growing right next to a soybean. When we say they’re truly competing for nutrients, it’s not just a root mass. It’s the relationship than the soil.

It’s important to call out that even though there are traits built into our soybean offerings from a post standpoint, someone’s got some residual to them. Those are our chemical control options, and based on where you’re geographically, maybe some of those options are tools in your toolbox. They might not be your go-to, but other options can support those chemistries to get that canopy that can drown out the waterhemp.

The ones that come to my mind are planting date to get that canopy closed sooner. We can change culturally to get our row spacings a little tighter. In some environments, I know folks have very good successes with the cover crops that are suppressing that early-season waterhemp flush. They’re also using the Xtend and the E3 technologies to help support all that. Collectively, there’s a lot of tools to go after this.

I love the cover crop idea. I’ve run across a lot of growers that they’re 100% with it or they’re 100% against it. I’ve had very good success in my little farming operation. I also have worked with a lot of growers that have had tremendous success with the cereals like cereal rye. It’s one of the simplest things you can work with. You can sow it relatively late after harvested corn.

To understand how a soybean grows throughout the season, you have to understand a bit of the internal processes of a soybean plant and how it works.

I’ve seen major reductions in waterhemp establishment early when you have that cereal rye crop out there, and it doesn’t have to be a tremendously thick crop either. That’s maybe some mistakes that folks try to make. They try to go out there with 120 to 150 pounds of seeds trying to create a very dense mat. I’ve had tremendous success with 50 and 60 pounds per acre broadcasting or drilled into corn stocks here as long as you’ve got a decent amount of time and October heat to get it growing. That’s a great tool.

You’d reference some of the essential nutrients that the plant needs that it gets free from mother nature. We have carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. What about all the other central nutrients? What do we need to focus on there?

We talked about what makes a factory run. We talked about keeping the lights on with the big three, the carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen but now we’re going to get into the discussion of the big bulk material that has to get moved the raw materials. That have to run through a factory to produce a car, let’s say. There’s a certain number of raw materials you have to have in order to build that car. On the other side of the factory, you have to have a factory infrastructure big enough to produce the output that’s at your end goal.

If I’m a car factory and I’ve been producing 100 cars per month for the last 2 to3 years, and the boss comes and says, “By the way, I shipped 2X the amount of steel and plastic, I want you to produce 200 cars.” Is that going to work if you don’t expand your infrastructure? Probably not very well. When we have this discussion about the rest of the nutrients, it’s a matter of whether they are raw material or actual factory builders, a plant process type of nutrient.

When we think about raw materials, the big two from a soybean bushel production are nitrogen and phosphate. When we think about 100-bushels soybean crop, depending on who you talk to, some are between those 400 and 500 pounds of nitrogen. About 325 to 400 of that is going to end up in the seed. Nitrogen would be classified as a total raw material. Just like in corn, you could put 500 pounds of nitrogen out there and not get 500 bushels at the end of the year unless you have a factory built big enough to get those bushels out there. Soybeans are the same way.

It’s a huge user of nitrogen. That’s a key raw material. Phosphate is another one. It takes about 100 pounds of phosphorous uptake to get to that 100-bushel mark of production. Out of those 100, 73 pounds, roughly, of that phosphorus is going to end up in the seed, and out of 20, 3 or 4 pounds is going to end up being used in the plant itself. Another one is a micronutrient, but its raw material is copper. Most of the copper you put on a soybean ends up in the seed. It’s a very small usage. The other big two that I want to talk about, they’re transitional nutrients. Let’s talk about potassium. It was first coined as the factory builder by my counterpart John Brien.

I heard him talk about potassium in terms of corn and its usage. About 80% to 85% of the potassium you put on a corn crop is used for the plant itself. Only 15% or only 15 pounds of that ends up in the seed itself. He coined that term quite a while ag, and we’ve just been building on it, but in a soybean plant, it’s about 50/50, about 50% of the K you use at the plant uptakes is used for building the factory and the infrastructure, and then about another 50% ends up in the seed. We often talk about the soybean crop as being a big potassium user. That’s because about 50% of that K you put on does end up in the seed.

Sulfur is another transitional nutrient. About 50% of it is almost dead, even 50/50 splits between being used in factory processes and factory infrastructure but then also being used and ending up as a final product being put into that seat at the end of the year. We’re talking about all the other micronutrients. Those are all factory processes, for the most part, nutrients.

They’re going to lean a lot heavier towards being in plant tissue, stem tissue, root tissue, making sure that all those hormones are engaging, activating and telling products on how to move throughout the plant. With magnesium, out of the 50 pounds of magnesium that 100-bushels soybean crop needs, 35 it ends up staying in the stover. That tells me it’s leaning a lot heavier towards factory processes.

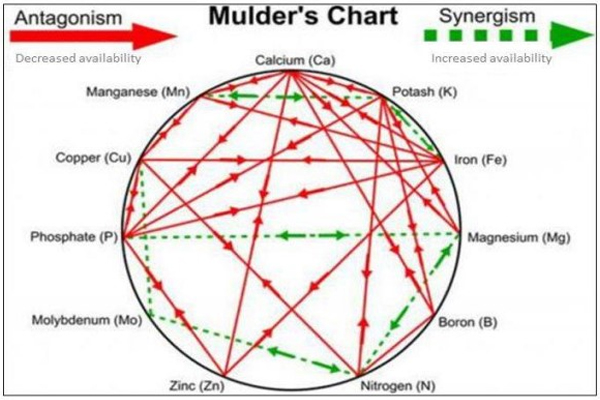

If you look at calcium, it’s a big one and key for a soybean. There are about 43 pounds of calcium. It has to be taken up by a soybean plant to get 100-bushels. Out of those 43 pounds, 39 of it stays in the plant. What’s interesting about calcium, if you ever get a chance to Google or look at Mulder’s chart, it describes the interactions of all the nutrients within a plant.

Calcium sits right at the top. There are a ton of arrows going to and from calcium. If we got to coin potassium as being a big factory builder from an infrastructure standpoint, calcium is the plant manager. It has so many defenses in so many different processes throughout the entire growing season, and a huge chunk of it ends up just being used by the plant itself.

With manganese, it takes about a full pound of manganese to produce a 100-bushel crop. 0.88 of that pounds ends up in the stover. Boron about 0.8 pounds per acre has to be taken up by the soybean plant. Almost 0.6 of that stays in the stover itself. Iron takes about 3 pounds of iron to get a 100-bushel crop. Two of those pounds stay in the stover. As we start to think about how we feed a soybean plant, we’ve got to keep the raw material discussion versus the plant process discussion in our minds. We’re trying to feed up a bunch of micronutrients at the far tail end of something.

The majority of those may be used totally in plant processes and you may have missed the boat. Likewise, if we don’t have enough raw material to get to our end goal, we’re going to miss hitting that high bushel mark. I know we talked a lot about just that one section, but it’s truly intriguing when you start to break it down and just, “What does it take to get it into the plant? What does it take to get that into the seed?” It’s pretty amazing to see the amount of nutrition a soybean plant has to take up per acre.

This could give some validation back to tissue sample projects. If we’re going off a soil test, we think our levels are adequate, and we’re not quite getting the yields that we want. A structured season-long tissue sampling protocol could almost give us some insights into which of these nutrients, whether they’re raw or just needed to keep the lights on which ones might need to be tweaked a bit in a given field.

We’ve worked as part of the AgriGold agronomy team with corn and saw the tremendous successes our growers have seen with a strategy of a season-long protocol. It’s helped them to try to make some fine tweaks and to improve their yields. With the soybean piece, we have started the soybean tissue sampling protocol and I’d encourage growers out there. If you have not tried this, try it because it will open your eyes to the differences and the timings these soybean plants take in nutrition.

Specifically, I’ll reference this as we talk about phosphorus late in the year as we get towards the pod fill discussion. If you’re not doing a tissue sampling program on some of your best fields or maybe some of your challenging fields, I’d highly encourage you to take the time or reach out to AgriGold DSM, our AgriGold Agronomist. We’d love to work with you all.

As we jump into the different quarters, the vegetative growth pod fills flowering. What are your thoughts going down those paths as far as some things we can tweak along the way?

The big talking point, the big buzz around soybean over the past 3 to 5 years, is, “When should I start planting?” We talked about some of what we’ve seen here in 2021, with the bigger pod counts on the earlier planting dates. Why is that? When a grower asked me, “When should I plant? What population should I plant?” My first question back is, “When are you going to start?” If you’re going to start planting at the end of May, you’re going to need a higher population. If you’re going to start the same time you’re planting corn, that’s when you can get pretty flexible on how much seed you put out there.

I like to put it like this. If you drop a seed in the ground on April 15th versus dropping it in the ground on May 15th, you have 30 days of growth. You have 30 days to build a bigger factory if you want to put it in those terms. You’ve got 30 days of good root development, more time to germinate, more time to get more leaf tissue out of the ground for photosynthesis. A bean in the ground on April 15th is going to be able to build a much bigger factory versus May 15th. If you think about May 15th, you may need two factories to replace the one that you started earlier.

If you go out to June 15th, it’s going to take a lot more factories because you’re just missing out on the time for actual growth and infrastructure building. It takes time to build a big infrastructure to produce a big yield. You either do it, get started super early, and build a tremendously large factory that can handle 100 bushels or you better put a lot of plants out there, a lot of stems, and a lot of little factories to try to get that same amount of output.

It goes back to your analogy on building the car factory. If we want to pump out more cars on the backside or bushels, we need to make sure we have that factory built on the front side. As the season progresses as to go later, we just need to make sure we have more physical plants, whether it be soybeans or car factory plants, you get the same output.

Exactly. It’s a matter of timing. It’s also a matter of the amount of fertility and the natural water holding capacity of those soils. Naturally, a fertile soil with that just perfect amount of pore space, airspace, mineral content, it’s going to be able to build a bigger factory no matter when you plant it versus a tight gumbo. In a really tight gumbo, we always struggled to get enough heights to get enough factory space on there. If you’re going into challenging environments, you’re going to need more plants out there no matter what time you start now. If you tend to go earlier, you can still reduce that down. What it comes down to are each individual growers’ circumstances. They know their ground better than anyone.

They know the ground where they lodge versus the ground that they always struggled to get up to even build up high. If you’ve got those situations in your head or those two different fields in your head, those areas that always lodged, you need less plants. That ground has the potential to build a lot of factory space with a lot less seeds per acre versus the incredibly challenging soil that has a hard time getting soybeans to put any height on. You’re going to need a lot more plants in that situation. One of the questions that we always continually ask ourselves is, “How big can a soybean factory become? How low can we go on seeds per acre?” We had the University studying this a lot.

If you look at replant charts, they oftentimes show that you can still achieve 100% of your yield goal based on planting date all the way down to 80,000. I’ve seen a chart from some of our other agronomy members across the country showing less than two-bushel difference from 60,000 up to 140,000 a plant population. The soybean plant can be very adaptable.

The other thing that blows my mind on a plant’s ability is if you give it the right opportunities to express its natural structures. We’ve got soybean plants that can flex as far as canopy and bushiness if you will. If you put a lot of lateral branches on, it’s 3520. It’s one of our best-selling Xtends soybean varieties. It was one of our original launches.

I don’t know how we got so lucky to do that, but we did. Some of our yield masters, they’re taking the 3520 down, the 50,000 plants per acre and different row spacings. I think of Jimmy Frederick in that Southeast corner of Nebraska in 2020 was able to get to 3520 yield 148 bushels. He did it was very low population. Some of our team was out there looking and taking pictures.

You need to have a factory infrastructure big enough to produce the output that’s at your end goal.

They were in populations as low as 20,000 but if you were driving down the road, you’d look out there and sort out that was just a perfect field of beans. You wouldn’t suspect a population issue at all, a low population or spotty stand. Don’t underestimate the soybeans’ ability to produce a very big and efficient infrastructure if you get it out there early on very fertile land.

To add and to support that, if we do go these lower pops for these higher yields, those particular growers aren’t giving up on the raw materials to help support that. Even though they got less factories out there, they’re still supporting it on the other side to make sure the output isn’t impacted, correct?

That’s right. You still need that certain amount of nitrogen per acre. The usage rate of a soybean plant at 50,000 per acre is still going to need as much nitrogen as if there were 100,000 seeds out there.

As we think about the establishment log, the performances that I’m seeing in the fields right now coming off trials are driving this early population. The one big key thing that we can change. However, planting early is all relative to your own geography. There might be times where planting early might need to be adjusted slightly.

The thing about going early is relative. You have to be a student of that 5 and 7 days forecast for temperatures. The one thing that I’ve come to realize about a soybean seed itself is that it’s very forgiving as long as you can get it to take in water. Our soil water that’s above 50 degrees has the ability to do. If you can get that done, you can put it into the refrigerator for several days and still come up with very good stands. Even more so than corn, that’s one of the big a-ha moments for me doing some different planting day trials from 2018, ’19, and ’20. I’ve put some soybean seed in some very stressful, cold, wet conditions.

In every instance, I was always watching for that 24 to 48-hour period where we catch that nice warm-up, where we can catch soil temperatures above 50 degrees. The neat thing about a soybean, all of us can experience this that works with both crops, is it’s like a sponge. It can suck in water relatively quickly compared to that hard waxy outer layer of a corn plant. When we talk about ambitional chilling on a corn plant, we’re always talking about a 48-hour window. You need 48 hours of at least above 50 degrees.

In order to get that warm soil moisture to imbibe by that seed corn, we can start the germination process in a healthy fashion. Now the soybean plant, on the other hand, can actually imbibe all the water it needs to start its germination processes in as little as six hours. The charts will tell you 6 to 24 hours. It’s nearly half the amount of time that it takes for seed corn to imbibe that much water.

When you’re thinking about if you’re playing that game, you’re crunching it, and you’re pushing the window, you’re going to be better off catching a 6 to 24-hour period of good warm soil water to get into that seed than you are at 48, especially if you’re going early April, especially in my geography. At the end of the day, that soybean is actually more forgiving from that early perspective of imbibing water. I’ve seen temperatures drop going from soil temperatures. I’m specifically looking at 2020.

We had an amazing run-up in temperature from about April 5th through about April 8th. I planted right there on April 7th and had just good temperatures from there. The soil temperatures dropped as low as 39 degrees and stayed below 50 all the way through April 20th. That stand was perfectly fine. There was literally no difference between the stand there and the stand planted on April 21st. Other than that, the unifoliate were out. The first trifoliate was out basically before the April 21st soybeans even fully emerged. The soybean plant could go through some pretty tremendous cold stress as long as you can take in that warm water right out of the gate.

Quarter one stand establishment that has influenced on quarter 2, quarter 3, and quarter 4. As we get out of quarter 1 going into quarter 2, what are some things we need to watch out for during this phase, as far as what we need to make sure we don’t do to negatively impact that crop?

A few things just as a caveat onto quarter one, make sure you’re using the available technology. The seed treatments we have are so much better than what we had few years ago. Specifically, when we think about sudden death. That hindered the early soybean planting movement in Missouri for few decades. Guys would try to go early and they’d see a yield bump. The next year, sudden death would come in and obliterate that crop.

A lot of growers ended up planting all their corn waiting two weeks, and then starting to plant soybeans around Mother’s Day, mid-May, trying to avoid the sudden death. With the seed treatment technologies that we’ve got out there now like Saltro and ILEVO, it lets you have the ability to try to push the envelope a bit more and not have to worry so much about the SDS pressure that once was a real negative yield impact.

In my part of the world, I’ve seen in the past few years an average of eight-bushel response, but I’m in heavy clays. That is early planting and that’s even planting all the way up to June. We’re an SDS hotbed for the country. If growers asked me whether they should use an SDS product like Saltro, I just tell them it’s a no-brainer. If you’re in my world, I’ve just seen it yield closes to eight bushels three years in a row. It’s technology that does work. Some other insights, too, we do a lot of seed treatment trials across the country. You just look at all the data that comes in and you look at the different bushel gains you get from using inoculant or using products like Saltro.

There are always these hotbeds, spots that show greater return versus others. One of the neat things that supports getting your first quarter started early is you can look at pretty much all of our data. If you break it out April 1st through May 15th planting dates, all of those seed treatment trials across the country yield at 71 bushels. When you look crack out that data from May 16th to June 15th, all of those seed treatment trials average 63 bushels. There’s another eight bushels gain right there just from starting earlier.

You can look at all sorts of other charts and areas of the PTI farm there in Illinois and Pontiac produces amazing data every year out of their book. I looked at their 2020 data, they pretty well recognized April 11th as their best planting date. That being averaged a little over 85 bushels and you jump out to May 14th year, all the way down to 65 bushels. Almost a twenty bushel gain on that highly productive soil by pushing your planting date up 30 days. You’re right. When you get that factory in the ground and get it started has a huge impact basically for the rest of the season.

On that SDS piece, even though that’s a decision that’s made at quarter one but we don’t know if we have a problem until flowering into quarter four. It’s some of these decisions that have to be proactively made. You just got to know in your gut and through data that it works and we could have a potential problem that it’s worth doing because there is no curative at that point to go fix it later in the season.

We’ll get to the last couple of quarters as being the most crucial for establishing yield, but there are just things that we’ve got to get done right, right out of the gate. It’s just like growing a great corn crop. Getting that stand out of the ground, getting the preemergent products down, starting clean, getting those plants out and growing, getting an early canopy, that’s how you lead to a lot of success like in the second quarter. The second quarter of growth is basically all about that early-season vegetative growth for a soybean plant. From when that first flower emerges is what I call the second quarter. It’s the most forgiving quarter that we have in that entire growth cycle of the soybean plant.

If you think about all the stress that we do as managers to a soybean plant during that early vegetative growth, I’ve seen growers burn the 2 or 3 trifoliate off of a soybean field using Cobra. If you go up North, they roll them with rollers and physically damage the soybeans to push the rocks back down. There are just all these crazy things that we do in that second quarter and the soybean yields right through it. Getting a good stand is the first step. Trying to get as much management done as you can in that second quarter is the next step because you can stress that plant.

You can spray that plant with big loads of chemistry. You can do a lot of stuff, and it’s very forgiving during that quarter. What you don’t want to do is take all that management, all those huge concoctions of spray solutions and push that into the third quarter, which is where the plant is starting to flower and starting as reproductive processes. Everything we’re putting on these soybean plants got metabolize. They’ve got to work through that and it takes a tremendous amount of energy to produce a bushel of soybeans. You don’t want to waste that energy with crop protection decisions and crop protection pitfalls that should have been done 30 days sooner.

On that one, as far as all the loading of different AI’s during that third quarter, the plant has to metabolize. The best way of an analogy, for me, was think of it like a debit card. The plant is wanting to go offensively but it has to take energy or currency out of the debit card, the checking account, to go process these active ingredients in the processes that we’re doing. That’s just not a time that we want to divert funds from the account because those funds need to be going to developing the pods and pod fill.

That third quarter, you think about what a soybean plant has to do once flowering starts. It has to not only start its reproductive processes, which takes a big load of energy, water, sunlight, it has to grow nearly 2/3 of its height still. If you think about that, that’s like building a very complex ship. As you’re sailing down the river, it takes all hands on deck. It takes everything going well to maintain as many flowers as you possibly can.

You can eventually get those to turn into pods if you’re out there during that time, just as you said, stress in this plant making it burn energy for the sake of tissue recovery from a hot load of insecticide rather than letting it focus on maintaining blooms. You’re hitting the debit card button. You’re hitting the debit on yield.

I’ve always had growers once R2 going into maybe some slightly R3 always get the question about, “I have weeds out here. Can I go spray some glyphosate on it?” I always cringe on it because we’re at that threshold where we could have problems, but then, what’s the problem if we allow those weeds to escape. It’s almost a toss-up which is the best decision to make. It’s planting through your quarter, so you don’t have to make that decision.

If you look at the charts and the number of days it takes on average to get to bloom, you’ve got about 51 days to get through the first, get up and stand established, and get up to about the 6 or 7 trifoliate. That’s typically when a lot of soybeans will start to bloom. You have about 51 days to get all this done. Think about that in terms of your spray program, “Are you getting it all done within 50 days of planting or 51 days?”

If you are, you’re doing a fantastic job. It’s in order to get done within 51 days, you have to put out some residuals and do some different things, but it’s totally worth it because you’re going to allow that plant to be cleaned, to start clean, to not have any competition, but also to start as reproductive processes in peak form.

When we get to the fourth quarter, it’s crunch time. When we start to look at just the sheer nutrient water demand that happens at that time, it’s mind-blowing. When we look at the first 51 days of a plant’s life, it’s only using about 14% of its total N, P and K uptake. That basically tells me with my Missouri math that that leaves about 86% of the N, P and K has to be taken up by the plant from flowering through maturity. That lasts 51 to 70 days. That’s the magic hour. That’s where all of this nutrition has to come into the plant in order to produce its biggest crop.

Fertile soil with the perfect pore space and mineral content will build a bigger factory, no matter when you plant it.

Very similarly, corn season-long supply of sulfur nitrogen, for these higher-yielding crops, that concept almost swings over to a soybean standpoint where we need to manage some of these high-end raw materials throughout the season versus just assuming it’s out there and it’s going to be taken care of.

It’s all about managing it ahead of time to get that soil structure and raw material load in a position and in the root zone so the soybean can take advantage of it when the time is dry. It’s hard to manage macronutrients through foliar applications. That’s the other thing. You can’t physically replace 50 pounds of nitrogen need with foliar trying to feed through stomates or plant tissue.

It’s going to take some other modes of action, some other management to try to get that much nitrogen into a soybean. The soybean plant creates nodules and its fixing atmosphere of nitrogen. That’s the biggest part of it. Nitrogen need is there. We’ve got to get it into position to be able to take all these nutrients right at pod fill.

When we’re in that flowering phase, I’ll call it R3, R4 but in your quarter 3, photosynthesis is still so very important and to keep it all those lives or at least alive so the energy can be converted over. That’s where if we have stinkbugs, bean leaf beetles and diseases coming in that can compromise that the I’ll call it the infrastructure of the factory.

The thing about that we have to realize is that 100 % of your success, if you are running a soybean factory depends on keeping the lights on. There’s no battery backup. You’re totally powered off solar. If you’ve got things diminishing your solar panels and infrastructure during this key time of flowering and pod fill, you’re hitting the money on the spot on yield. Even if you look at all the university IPM charts, it takes a lot more leaf damage during that vegetative growth to necessitate a spray and those percentages of acceptable feeding go way down when you get to pod fill because it takes a lot less damage at that point in time to cause a lot more yield damage.

Would you say that in recent years or even maybe on the growers that are shooting for these 120-plus bushels per acre are incorporating more fungicides into the management practice basically to preserve that infrastructure and those solar panels during this time?

No doubt in my mind. Insecticide at the right timings, maybe even multiple insecticide applications and then getting that infrastructure protected with the fungicide to keep that plant alive and doing photosynthesis as long as possible. It’s imperative if you’re trying to accomplish any yield goal bump at all in a soybean crop, in my opinion.

You referenced that in quarter three, moisture was so very important. That’s when the peak does come into the soybean crop. They always say August rains make beans. How do you plant for that or can you?

Planting around the weather is always difficult. We could all agree to that. Even if you look and do your best plan possible, Mother Nature will always throw a wrench into it. The best way to diminish a soybean crops potential is to starve it for water at pod fill. That is buying large. The number one factor for achieving good yields is having water available at pod fill. The water usage peaks right there in late July.

The water intake 0.3 to 0.4 inches per day on a soybean plant of 80. If you’ve ever had the pleasure of seeing dryland soybeans verse irrigated, it’s 20 and 30-bushel difference. I see this in Nebraska when they have dry years. It is amazing the amount of just some critical inches of water at pod fill can do for a soybean plant.

No matter what your planting of attack is, whether it’s planting date or it’s maturity, your number one goal should actually be based on the ground you’re going into. How do I either pick my planting date or pick my maturity to maximize water at pod fill? I’ve got growers that will argue with me in Missouri on very challenging soils that they cannot plant early. They have to plan basically after Mother’s Day because, after Mother’s Day on their tough soil, they can almost guarantee that late August rains will come in and they can achieve a 45 to 50-plus bushel crop.

For them, that’s their management style. That’s how they ensure that they get water at pod fill on challenging dry land. On the flip side, if you’re doing that management on your very best acres, your good water holding capacity, creek bottoms, river bottom soils, you’re given up that big bushel gain from getting that factory started sooner. That’s one of the challenges I see with that mindset of trying to go late and catch the late rains.

A lot of times, I have conversations with growers that “planting early” is all relative to their geography and similar challenges. There have been some times I’ve had an ice back from planting way too early in some environment. Just because we say “plant early” it doesn’t necessarily all have to go plant the last week of March. It’s all relative to our own geographies. It might just be planting a few weeks sooner versus taking a big month jump up.

Always keep that in mind. It’s very important. We spent a lot of time talking about the overall factory and the different quarters that we can try to influence throughout the season, whether it be stand establishment, the vegetative growth, the flowering pod fill. What are some final thoughts that you have collectively that some growers could be considering as they go into the 2022 crop?

We talked about tissue testing a while back. One of the things that I’ve seen, and it’s in regards with water availability of pod fill again, but understanding that you have to have water to get the phosphorus and the nitrogen if the seed is big. By tissue testing, it’s an a-ha moment looking at making sure we’ve got enough FOS in the ground to achieve 100 bushels. Whenever I was looking at particularly the phosphorous levels in a plant in R3, R4 phase, 2,000 GDS to about 2,400 GDS, we had yields from 45 bushel to 105-bushel in this chart. The amount of phosphorus in the leaf tissue was almost exactly the same for the 105-bushel and the 45.

The key difference was the 45 bushel flat ran out of water. It did not have enough water to get the phosphorous levels up into the seed for it to create a bigger bushel grain. Likewise, the 65 bushel and the 85 bushels had more water to work with, but legitimately, they didn’t have enough phosphorus for high yield as where the 105-bushel zone had enough water and had enough raw material to crank out 105 bushels.

Final thought, if you’re going to try high-yield or early planting, pick your best acre. You’ve got to pick your best acre if you’re going to maximize building that factory to its biggest capability and your best taker also is going to have the ability to have more water-holding capacity to ensure that water at pod bill so all that hard work you’ve put in can actually come to fruition in the form of bushels.

There’s a source-to-sync relationship we need to think about. Whenever that soybean plant transitions to starting to form that seed, all of its energy and the flow of nutrients in that plant goes from keeping the plant alive and green to sucking leaves dry and putting it towards the seed. Somewhere in that beginning of pod fill, maturity and leaf drop, there is an opportunity to take advantage of the source-to-sync relationship? Is there a missing micronutrient? Maybe out of those 3 pounds of iron, 2 is going to go into the foliage.

Maybe you need that extra pound of iron on there or you can get that and give then to the seed so we’re starting to see some pretty good relationships in some of the testing that we’ve seen on doing some more foliar-applied type things, particularly around solving micronutrient shorts. It’s around quarter 3 and quarter 4 to take advantage of that source-to-sync relationship.

If you haven’t thought about that and you’ve hit some yield barriers, maybe that’s an avenue. At the end of the day, you’ve got to take advantage of heat at the end. I’ll never forget it. As we started to launch soybeans, we were working with a soybean plant breeder. We were out in the field doing the training in Central Iowa and that soybean product guy said, “Soybeans don’t care if it’s 90 degrees as long as they’ve got water. In fact, I almost think they actually prefer a little more heat than they would the cooler temperatures as long as they’ve got water.”

Whenever I think about the key to polish off a super-strong soybean field or soybean yield, I’m thinking about a good warm and sunny finish in September. Let’s say that heat is 10 degrees above average. For every 10 degrees, you raise in nature, you double reactions. If your soil temp is 60 versus 70, at 70, you can almost get a 2X rate more mineralization just because of the laws of thermodynamics and how that Rule of ten works. If you have more heat in September and you’re filling a later bean crop, you can actually get more mineralization, more nitrogen, more phosphorous to the seed.

That’s also one of those tricks that some of these high-yield guys are doing by planting earlier. You’re starting flowering sooner and you’re taking advantage of more sunlight. With peak sunlight, solar radiation peaks in July. It starts in June, peaks in July, starts to decrease in August pretty much for the entire Midwest. If you can start flowering on June 1st instead of June 20th, you’ve got a lot more sunlight. You’ve also got a lot more ambient temperature, nighttime temperatures, and everything. As long as you can keep the moisture to those beans taken advantage of good warm temperatures is going to give. It’s really the trick to finishing off a very big soybean meal.

There is another great conclusion there on some great insight, a lot of things we can’t control, but there are a few things we can control along the way. If I had to just think of the overarching theme of this talk when thinking about growing soybeans, think about Henry Ford wanting to produce more cars and trucks. He had to make sure that the factory got bigger before he could pump out more cars and trucks but he also had to make sure the light stayed on, and he had enough raw material there.

If we are shooting for higher yields, we just got to make sure those raw materials and the overall factory have the capacity to pump it out on the backside. With that, Dustin, I greatly appreciate you joining us again. You’re always a wealth of knowledge and I do enjoy chatting with you on agronomic topics like this.

Thanks for having me, Tom.

For every out there, thanks for tuning in. We’ll chat with you next time.

Important Links:

- AgriGold

- Dustin Bowling – Previous episode

- Braungardt Ag

- John Brien – LinkedIn

About Dustin Bowling

Dustin is from Chillicothe, MO, and is the AgriGold Western Agronomy Manager, as well as our resident soybean expert.

Dustin is from Chillicothe, MO, and is the AgriGold Western Agronomy Manager, as well as our resident soybean expert.