Farming and agriculture is a challenging, vital, profession. Many factors can make or break a crop. Todd Steinacher joins today’s guest, Joey Heneghan, AgriGold’s Regional Agronomist for Wisconsin, Illinois and Minnesota, as they discuss the many challenges faced in modern agronomy and how to face them down. Joey shares his insight on fertilizers, weed management, herbicides, and soil conditions. Tune in to today’s episode and learn how you can equip yourself and your farm with the best tips and increase its yield.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Let’s Dive Into The Weeds: Weed Management In 2021

I’d like to introduce my guest, Joey Heneghan, a CCA and a regional agronomist with AgriGold covering Wisconsin and Southeast Minnesota. Joey, welcome to the show.

Thank you, Todd. I’m glad to be here.

How about you take a few moments and tell us about yourself and your family? What brought you to be an agronomist within AgriGold?

I’ll start with my family. I have a wife and a one-year-old daughter. We live in South Central Wisconsin right between Madison and Milwaukee. I grew up around agriculture. I loved doing that. My grandparents had a farm. I also worked with farmers all growing up. I was influenced and had that around in my life. What brought me to the agronomy side specifically? I liked technical subjects in school, math and science. I loved being outside and be able to do things with my hands as well. That’s where I saw the greatest blend of getting that agricultural feel with agricultural work, but be able to work with some of the more technical topics, the science of farming. It’s been a good blend with professional freedom to be able to have that technical eye. Professionally, the way I look at farming is I get to help farmers do a better job of what they’re doing every single day.

How about you give us an overview of the territory that you cover for AgriGold?

The southern half or southern two-thirds of Wisconsin, more or less the economic region of Wisconsin. The northern part of the state is beautiful, but there’s not a lot of corn and beans up there so I don’t officially cover those areas. Also, Southeast Minnesota, roughly over the I-35 Interstate back east to Lake Michigan. That’s my part of the world for Agrigold.

Those parts of the country seem a little bit more challenging than down to where I am at. Central Illinois got a little more roll to it. The rock layer might be a little shallow. What are some challenges that producers face in your part of the world that you get invited into to try to help offset these problems?

There are definitely challenges. Top of mind is our short growing season. It quickly drops off from that Illinois state lines. You start working north through Wisconsin and the tri-state area of Iowa. Minnesota, Wisconsin, working north from there. You quickly lose growing season as you work north. That’s a challenge every single year. I call it fragmented topography. We’ve got areas that look like you are in Central Illinois or Central Iowa with fewer rolling hills or flat black areas.

Go half the county over and you quickly get into tough lighter sandy soils, tough non-glaciated or ancient glaciated red clays to completely non-glaciated areas where bedrock is much common than topsoil. Across that whole area, there is a lot of role and variability. There are some beautiful high productivity regions, but there are also a lot of challenges. Central sandy Wisconsin without irrigation is very tough to grow more than pine trees there. I get to cover all that wide-ranging area from natural fertility and natural land. What makes you a good manager is to do a good job at some spots so it’s a great challenge.

In roles like ours, were always brought out to work on challenges. Very seldom we have to come out and look at the best and greatest looking field. I always tell growers, “If I come out and look at a challenging field, I expect a phone call later that summer to go walk a good field.” I’m sure you’ve been in those situations. It’s nice to get called out on some of these challenging situations so we can help somebody. One of the reasons that we probably all get into the career that we do is we like the technical aspect as you referenced, but we’d like to help people. From your standpoint, being an agronomist in your territory, is there a situation that stands out where you were asked to come in and help with a challenge or a situation? When you left you’re like, “I helped these guys out,” and it’s a great feeling.

There’s maybe one or a couple in particular that related to us. We do have a big proportion of conventional corn acre in this geography. A lot of it is a cultural practice. Maybe we’re never forced to grow treated corn either for weed or insect issues, but we still have a lot of conventional corn acres even in 2021. With that comes challenges and occasionally you do get breakouts, whether it be worms, corn borers, corn earworms.

One call, in particular, I was working with a customer that was familiar with how they were growing conventional corn. They understood the risks and also the best management practices. I remember walking in the field late in the fall, I nailed one field. There’s one in particular, I got on the ear shanks and look at that plant and the ear would fall off of it. I was talking through with that customer and they knew the routine for scouting. This is a tough situation, sometimes the realities of farming agriculture. They took the Fourth of July weekend off and a lot of us prefer to do that. That was more or less the time period when the corn borer came into that field and laid eggs. They found the egg masses after the Fourth of July and were too late in getting it sprayed and application light up. The eggs already hatched. They got into the plant before they got sprayed. We saw the aftermath of that fall. It was too late to make an impact that year, but in that particular situation, we honed in.

Unfortunately, corn borers don’t care when the Fourth of July falls. If we’re going to grow conventional corn in high-pressure areas, you’ve got to have your timing, applications and scouting on the spot to make sure you get that done well. That’s one example. There are many like that, sometimes corn earworm or corn borer, but we still have a lot of success growing conventional corn here with historically low insect pressures and good weed control. Not necessarily needing treated corn for either, but it’s a challenge and a topic that I field a question on every single year. How do we successfully grow conventional corn or continue to grow conventional corn in this geography?

A lot of it is cultural, but here and there are premium options available either for non-GMO dairies or just non-GMO markets that exist on the Illinois River, south of the Mississippi River through the middle of my part of the world. That is an annual question I receive that helps people and at least helps guide them on scouting and application options, and what to be looking out for on their commercial corn acres.

Most pests out there don’t have a calendar or in tune with what’s going on in society. When those major holidays come up, it seems like that’s when they’re doing most of their activities. It gives great insight into the value in scouting and being proactive with scouting, regardless of what’s going on the calendar, pests, insects, weeds and diseases don’t care. A high percentage of conventional corn got to stay aggressive from a scouting standpoint, be proactive as much as you can. You referenced that a lot of guys have opportunities to raise high-yielding corn and there are things we can do to manage to influence those things. As you’re working with growers to get higher yields, what would you say are some strategies that they implement, very specifically from a nitrogen standpoint?

From a nitrogen standpoint, I’ve learned a lot and it is variable. I referenced the I-35 area in Minnesota, which is where it flattens out. From there on the west, we get some great soils in Minnesota. I don’t get to play with those very often, but I do have some customers. East of I-35, we’ve got truly heavy, flat, black, silty or straight clay loams. They don’t beg for split application nitrogen. I like split applications of nitrogen. It’s a great practice to try to limit the nitrogen losses and oftentimes is the best management practice.

I’ll be the first to admit that some of those heavy soils can hold a nitrogen load for an entire season. We can front-load those soils with nitrogen and they hold it, then our crop has access to it. In those situations, it’s a little bit of an easier answer on that side of things. I’d say most of my geography, working with silt loams, silty sandy loams, more straight sand, that split application nitrogen is essential in those situations. We can’t hold things much more than oftentimes a month if maybe two weeks on the worst of our sands that are irrigated. We’ve paid a lot of attention to how do we do those nitrogen applications.

A big conversation in the past few years is the sulfur component as well. We’ve cleaned up the air and many industries have been mandated. We‘ve done a better job on our sulfur emissions. We in agriculture now have to buy sulfur because it’s not a free nutrient that we get from emissions or in the atmosphere near as much as we used to. That’s something that goes hand in hand with that nitrogen as well. That’s a big conversation. I had conversations with farmers in the past years who have applied the first sulfur they ever have on their farm because they realize that’s something that they’re not getting anymore. It’s nice to go hand in hand with their nitrogen.

I like display applications, most of our soils can benefit from it or we can use slightly less nitrogen across two applications compared to one big dose, but the sulfur component goes with it as well. I’ve got farms that got a 250-bushel expectation on the flat black ground, and they can do it with one shot upfront. I’ve got farms that have a 250-bushel expectation on sugar sand and they’ve got to spoon feed it 4 to 5 times throughout the year through the pivot and other applications, side-dress, dry upfront, etc. They can both achieve those yield levels through drastically different strategies, a lot of it being nitrogen.

You described almost polar opposites of how soils are going to supply the ability for these yields to obtain them. With all the variability up there, you can’t have a cookie-cutter approach to things. It has to be specific to that farm and be willing to recognize the limitations, whether it be because of the sugar sands like you referenced or these different types of clays that accomplish throughout your territory. How do you have a conversation with the grower on wanting to step out of their comfort zone, call out these limitations, and try farming a little bit differently very specifically to splitting nitrogen or using sulfur? How do you have that conversation?

I’m far from an expert on anything. I don’t like to try to use myself as that term, but what I can offer is someone who travels between I-35 to Lake Michigan sees a different number of cultural practices that work across soil types. I bring up what I saw three counties over and say, “Farmer A, 75 miles away does this and it works. That’s something that’s not done around here, but why don’t you give that a shot. There’s good reason to think it would work because they’ve had success with it.”

One of the biggest, most powerful experiences I’ve had is being able to translate or communicate different strategies that don’t jump across county lines and state lines or outside of projected growing areas. Many people don’t travel as far as you and I do, Todd, and that’s fine, but it is something that we can bring to the table. It’s a shared experience that we see from our big geographies. That’s the way I’d first open up those conversations and usually back it up with some experience or success stories or reason as to why you might want the split application into these soil types. I can almost guarantee some of that is being lost and it’s not good for your pocket, the environment, etc. There are multiple reasons to try to do that, but if you can tie it back to your success story for that farm, they oftentimes want to do the better job. That’s the way I approach those conversations.

I like how you’re using your experiences as you travel and try to help influence and tell those stories to producers. You’re selling yourself short. You’re a good expert in your field. I like how you’re humbled on sharing insight and information up there. When I was in college, I worked up to your neck of the woods for summer in green beans. I remember being in some parts of it that they weren’t able to use a lot of deep tillage or even anhydrous that I’m used to hearing only because the rock layer is so shallow. How does something like that influence applications?

I’ve got pockets of anhydrous usage, but some areas don’t flourish out there. That bedrock issue being one of them or cultural pockets. On the nitrogen side, we have to plan. I say most of my areas, predominantly either liquid UAN nitrogen or urea. Now we’re getting a big splash of AMS or ammonium thiosulfate liquid side for our nitrogen sources. In terms of how we do that, our field size and field shape are much of a determining factor, sometimes as anything else. You got a lot of fields that are hard to side-dress because they’re either shaped like a broken dog leg or they’re so hilly that you can’t dependably drive these things much past about V6 because they’re so steep and you can’t stay on the road no matter what you do.

In those situations, if they’re lighter soils, the biggest challenge is, how do we still split a pair of nitrogen or get stable nitrogen out there, when we can’t effectively knife in or culture in liquid? In that case, we’re oftentimes top dressing with urea and AMS, which is a little bit risky but oftentimes is the best option in these fields to try to get a split application out there. Get it out later than planting later than V2 yet still trying to get a good spread pattern and not volatilize it off the surface as well. There are a lot of conversations and more than 1, 2, or 3 options and more than one way to skin that cat.

The topography, the cultural areas, the field shape, size and soil types often define when do we put out UAN and how do we use it? Do we use dry urea? Is it upfront? Do we try to top–dress it? I prefer to get nitrogen in the soil as much as possible, but my options are to put it all upfront on sand or split it in top–dress later on. I’m going to trade that top-dress option every time and try to hope I can have it later in the season that way. There are a lot of factors. It’s hard to put anyone option on it, but that’s the way I usually start approaching those.

I liked how you referenced several fields that look like a broken dog’s hind leg. It can be challenging with some of those fields, from a planting standpoint, from applying certain crop nutrients or even from a disease management standpoint. It’s hard to get an aerial application to spray a fungicide for corn and soybean. Some of those challenges play into needing to make very good decisions. From a hybrid and variety standpoint, you were challenged to get a full season of GDUs to allow that season to bake the corn crop. From a hybrid variety standpoint, how does that short season influence some of your decisions, and knowing some of these fields maybe have some challenges to get in a side-dress application or being able to spray a fungicide on it?

In terms of the fungicide question or disease question, it’s a question that I’m asked and considered up here. We’re in an area, for example, the southern third of my area is pretty hard in the past. It’s something we’re watching out going forward. If we’ve got a field that is not realistic, I’m able to either get it sprayed with the ground rig, or there are power lines, there are too many trees to get a good aerial application. Hybrid selection for disease pressure, particularly on tire spot in that situation is going to be almost the number one determining factor. We know that our best management practice of applying a fungicide isn’t possible. At that point, we are purely at the hybrid selection. It is a factor that comes into it. In terms of season length, it’s always a tough situation.

I’ll reference 2018 to 2019, which we’re both later for planting seasons. We got to start swapping hybrids. If we were pushing what I would say our full-season corn, we have to start thinking about swapping hybrids by about May 15th to May 20th and deviating from our original plan because we have lost at that point enough heat units. We’re not going to dependably finish a full season hybrid for even any area beyond that date and encroaching upon June 1st or so there. That was a tough decision.

Particularly in 2018 and 2019, we had to start swapping corn. It was the right thing to do. If someone had planned on planting 105-day corn in Central Wisconsin, you get it in the first week of May. That’s dependably going to make a good crop. It’s going to be good. We’ll have to dry some of it, no doubt, but it’s going to be good corn. You go put 105-day corn on May 25th or May 30th, that’s not dependently going to be good corn anymore.

That’s guaranteed to get frosted as a finish, and then you have a lot of green quality challenges. Those are real things. We always have to balance what corn maturity do we want to try to push to yet balance our yield expectations, balance our corn drying expectations, and then the pure risk management of, can we get this corn dependably to black layer and ideally get a little bit of dry down before it turned cold for the year? It’s always a challenge here. We can grow awesome crops. Our season and Mother Nature definitely can make some last day decisions or changed some plans that we cannot always predict.

We can have the best plan laid out agronomically, profitability, best hybrids, best of everything. Mother Nature at the end of the day has the final trump card. I think we have to proactively build flexibility with the products we have or options that we’re able to do. Sometimes option A is not going to go in across all the acres. We have to have a very good option B. I think it’s good to be proactive in those situations just so we’re not caught on the wrong side of the coin that can ultimately end up with lower yields, higher moisture corn, and ultimately lower profits. It’s important to be proactive with both your primary option as well as your backup option. There’s a lot of agronomic projects going on around AgriGold in cornfield and soybean fields that helped to shape some recommendations or greater insight. I want to know what your thoughts are on some of the agronomic projects that you’re working with customers that try to move the needle for higher yield journeys.

This is pretty common across AgriGold and maybe the greater agricultural industry, be the flag test. That’s been a lot of fun for us in this part of the world. It was born in the southern corn belt where they do get some warmer soils and dependably good planting conditions oftentimes. The rule of thumb is you want to have all those plants up within 12 or 24 hours. That’s what everybody is shooting for and that’s a gold medal on the flag test.

I have a lot of fun with that. We oftentimes push the envelope on our planting conditions, planting temperatures. We don’t usually get a lot of corn that emerges quite that fast as they do where the flag test was born. I’ve backed up and done the math on it. I like to look at flag test more as a heat layer or a heat unit time and like to see all the corn up within about 10 to 20 heat units, which on a warm day is about one day.

In our spring, it will take us 3 to 6 days to get 20 to 30 heat units. I had guys who have done flag tests with ten different colored flags and they think they got awful results. They’re not spectacular to take ten days for corn to emerge, but from beginning to end, we only had 25 heat units because it happened to be a cool week. There’s a fun conversation to be had with that. We are looking for better emergence or maybe we just planted too early in that situation, or we still got a good final stand. We still need a consistent ear line and consistent ear counts. Maybe that spread of 20 to 25 heat units across those five days, that’s still an indication of a successful emergence situation and successful planting, but we just can’t measure some of that stuff.

For us, we had to reference it back to heat units so that we can compare our results to where you’re at in Central Illinois or where someone else is that, in Kentucky or Tennessee. It’s fun having those conversations and making people realize that sometimes we don’t get a single heat unit in early May. That corn is sitting there and didn’t have any chance to grow even by textbook standards. That’s been fun on the flag test side of things and a fun conversation that makes people realize some of the challenges of cool springs in the northern corn belt.

We get a lot of tissue sampling over the last few years. That’s been eye-opening and a huge learning experience for me. It’s a huge learning experience and also can almost be a black hole. It’s you trying to answer one question and you end up generating twenty more. It gives such a good opportunity to see if there’s a link or a disconnect between your soil fertility and the job you’ve been doing on that and to see if it’s translating into the crop you’ve got. It also gives you an opportunity to try to fix those problems, whether it’s this year or then implementing a plan for the future. It’s been a great opportunity to work with many customers in terms of answering those questions, trying to do better, and not necessarily always putting on more fertility, but trying to figure out what fertility do we need? How much and when? Is what we’re putting on is showing up on a tissue test? How does that show up on the yield side of things? It almost generated more questions and answers, but it’s given us progress nonetheless, in terms of trying to be better managers and better understanding the crop that we’re growing.

The tissue samples have generated a lot of insight for us, but it seems like it almost forces us to ask more questions than we have answers for. I was able to use this with customers to better understand what nutrients have a season-long demand. A lot of times we were front-loading products, specifically nitrogen, and throughout the season, we’re starting to drop off. We don’t have enough on that backend to support grain fill and all those pieces. It has challenged me to evaluate how we make recommendations. It can change season to season, but one thing it has done is it’s brought another layer of focus for growers to look at their crop.

Instead of saying, “I put nitrogen out there or PNK and sulfur,” the box is checked and let’s just wait until we get the harvest, and assume that all of our staves are full. In essence, it’s telling us in a scorecard that the plan that we have based on that field that season is not quite enough to get where we need to. I like how it challenges us to take more focus on what we’re doing. If we are seeing a particular nutrient drop off, hopefully, the next question is, “Why? What can I do differently? What different products are out there? How can I offset a lot of these things?” I do like the questions like this that typically follow these processes. It made me a better agronomist myself. Hopefully, you’re feeling the same thing out there as well.

I’ve gotten a whole another education just on fertility from the work that we’ve done on the tissue sampling. I’ve got a lot to learn, but I’m also a little more comfortable to have that initial conversation at least ask a couple of questions now with customers in mind and see where we can go with it. It is always a learning-together process. I feel like it’s a good conversation to have. I learned a lot from customers. Hopefully, I brought it to them as well. It’s been great.

These tissue sample projects have been a great partnership across our footprint with customers and within the agronomy team. I look forward to seeing the results of the coming seasons and how we can make recommendations. In grad school, you were in weed science, projects and categories. We start looking at different products in the marketplace. There are active ingredients and different trade names and everything. We start seeing things that reference the mode of action, site of action. Sometimes these words get interchanged and not quite understanding. From your standpoint, could you describe the difference strongly to a grower level, the difference between a mode of action and a site of action?

The site of action is where, and the mode of action is how. A mode of action we can work with would be pigment inhibitor. What pigment inhibitors do, two groups fall under that. They’re your bleachers. The ones we’re probably familiar with would be your Group 27. That’s very common, a quarter of the sides. Isoxaflutole, tembotrione, more popular than mesotrione, Balance Flexx, Callisto, Laudis are herbicides that when they hit plants they turn them white. They inhibit the pigments. Pigments being the green chlorophyll there. There is another group of those that many people may recognize as Group 13.

It’s an older formulation used in specialty crops. The active ingredient is chromosome, but it can also turn things white. If you apply it incorrectly, it can volatilize and can turn entire tree lines white if you do it wrong. Both of those are the same mode of action, they’re pigment inhibitors but they fall on different sites of action. One of them is Group 27 HPPD inhibitors. One of them is Group 13, which is the Diterpene synthesis inhibitor. We don’t have to worry about that so much. The site of action is where. That’s the bleacher part of it. A pigment inhibitor is the how, where they specifically hit. They’re not quite interchangeable. They’re very similar. It’s hard to make that strong distinction. That’s just one example of you have two groups that are the same site of action, but two different modes of action in how they achieve that result.

When resistance started becoming more popular from a roundup standpoint, a lot of folks were recommending multiple modes of action, change up our action site. It aggressively went to let’s change our sites of action to even change up where it’s happening. What are your thoughts from that standpoint?

The more variety we can throw at weed populations, the better it’s going to be. Herbicide resistance and natural evolution thing, it’s not an intelligent thing that these weeds are doing. They’re not thinking, “What’s the next thing we’re going to do to try to get a herbicide resistance?” It’s purely a numbers game in some little random mutation somewhere that happened to make the first water hemp plant tolerant to round up. If that plant had ever got sprayed with Roundup, they wouldn’t have helped that plant one bit. It’s a random mutation that would have passed on and they would have been advantageous. Because that field got sprayed with Roundup and that one plant survived, all of a sudden, they had a huge advantage over all its neighbors. It got to live. They got to make seed and its generations in.

That’s how we work with resistance. That’s how it works. It’s a random numbers game. The more variety we can work into our weed control systems, and particularly our herbicide systems for that matter, the more chances of us not lining up with those random mutations that nature happens to create in a random fashion. I’m all on board with trying to do as much as we can. Herbicides just one of the tools that we manage with but within that toolbox, we use as many different little hammers as we possibly can and try to have as much variety in there as possible.

It seems like Group 15 herbicides are very popular in both corn and soybeans. We know that it’s not a good long term to be having the same group out there year in, year out across different crops. A lot of times, growers don’t know that they’re getting a particular Group 15 because they feel that the brand name changed or there’s a premix product where maybe they’re going after the active ingredients but they didn’t know the Group 15 was in there. What are some recommendations you give growers on what to analyze in their programs to make sure they’re not consecutively using the same Group 15 in corn and soybeans because it is a valuable product for both crops?

Group 15 show across many corn and soybean premixes. Independently, they’re both crops benefit from having that class where herbicide’s available. We’re talking about the Dual Magnum. That’s S-metolachlor. Harness and Warrant are acetochlor. A little bit newer would be the Zidua and Outlook. Zidua’s pyroxasulfone. Outlook’s dimethenamid-P. All work in the same group. Something to be aware of when you’re working with those, try to mix up what you’re working with. All of them can go across both crops, which gives them a lot of flexibility but also does give you the opportunity to not use that same active ingredient year after year. You don’t have to use Dual Magnum in both your corn and your beans. You don’t need to use acetochlor whether it’s Harness or Warrant across both your corn and your beans. You can try to segment one each crop or at least vary up which active you’re using across your two crops if you’re strictly a corn-bean rotation, which is the most likely situation for this group.

One thing about this group is its fairly complex chemistry in the way they work in a plant. Resistance is slow to develop but we do have resistance. It’s probably not going to progress as fast as Roundup resistance or even the growth regulator resistance that we’re probably seeing as well but it is here. It is present in water hemp. It’s in the Midwest. We’re going to be working with it. At the very least, change up which active ingredient they are using. Those four that I mentioned being the most common. As you said on the premix, also pay attention to what rate you’re getting in the premix. Not every single premix necessarily maximizes the rate of every active ingredient that is in it or may only maximize one of them.

It’s common to see a premix that’s got a full rate of mesotrione or Callisto as one of the components, but sometimes they short the Group 15 that’s also in that mix. If you apply that alone, you’ll be allowed to apply more than what is in that premix when you hit the premix max. Some people will spike in a little bit extra to make sure they’re getting that full rate, but it takes a pretty savvy applicator or recommendation to know to look for that. That’s something to be aware of.

Use Group 15 as much as you can. If you’ve got a clean farm or clean area that you did a good job for ten years, you can try to get away with not using them. If one of your crops got a good herbicide plan or other actives available, try to leave it out for a year. That’s one more way to vary it up. Maybe some of those susceptible resistant ones can grow and then be killed by another active. Trying to always stay one step ahead. We’re rarely ever successful. Mother Nature always bats last, but these are some strategies, particularly on that group that we lean on a lot. Thankfully, we’re still doing a lot of heavy lifting, but the more and more reliant on it, the quicker and faster we’re going to keep finding resistance to it as well.

From a farmer and agronomy standpoint, there’s a lot of challenges out there. We’ve got to stay ahead of the game for Mother Nature just to make sure that we’re not behind the eight-ball. We can talk about new hybrids, fungicides and splitting nitrogen, but at the end of the day, if we’re not controlling our weeds, we’re disallowing another crop out there to take advantage of all those pieces and ultimately hurt us from a yield standpoint.

I want to bring up another area of this, diving a little deeper to segregate the difference between large–seeded broadleaves and small-seeded broadleaves. I know certain chemistry favor one over the other and I know that tillage and the amount of moisture we have can also influence this. A lot of times I hear growers say, “That new chemistry didn’t work because XYZ weed was out there,” but then you find out that it wasn’t on its label, it was going after a different style of a broadleaf. Can you hit from a high layer deep down the difference between large–seed and small-seeded broadleaves?

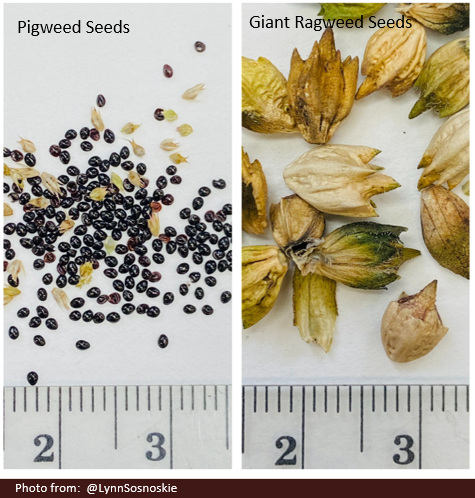

From my perspective, I look at it as I reference back to Group 15. It has traditionally been thought of as doing the heavy lifting on small-seeded broadleaves as well as grasses. It’s generally small seeds. Those that are usually weakest would be large-seeded broadleaf. Large–seeded to me is with a broad brush, giant ragweed, cocklebur, cucumber, Morning Glory falls in that category. It’s on the smaller side of large but it is large enough. Those four are probably the quintessential large-seeded broadleaf plants. Generally, those are not going to be very well controlled by Group 15 soil-applied residuals.

Those small-seeded broadleaves, water hemp, Palmer Amaranth, Lambsquarters, Marestail would catch 95% of your small-seeded agronomic broadleaves. Those are generally controlled well by your Group 15. Large-seeded stuff, we’re targeting those from the soil side with some of the PPO ingredients, oftentimes on the soybean side. The corn sides of our Group 27, the bleachers, we have Callisto, tembotrione, mesotrione. Those are a little better on the large-seeded broadleaves. You need to be aware of, on the broadleaf side, what particularly you’re going for.

If you’re going for waterhemp and giant ragweed, you’re probably going to look at two active ingredients to achieve that. There are not many single ingredients that can knock out giant ragweed and waterhemp from a soil residual side. Even getting to the point where post applications get a little more challenged as well. It is a good distinction to make and something to be aware of. What is your target weed and what ingredients are truly going to be effective against them?

From a large-seeded broadleaf, I was always told that they may germinate a little further down. They may have a longer survival rate within the soil. The plant maybe doesn’t produce as many, whereas small-seeded broadleaves merge little shallower. If we do tillage, we’re going to keep them towards the surface area. The plants do produce a lot of them. Would you agree with most of those statements that moisture and tillage can interact which one of these we can have more problems with?

Some of my grad school work was actually on waterhemp particularly. We did a seed longevity study. Most of what we found was that after 4 to 5 years, if your waterhemp seed, a small-seeded broadleaf is left on the surface, those seeds either germinated or degraded to the point where they’re no longer viable. If you can manage your waterhemp well in a no-till situation for 4 to 5 years, you’ve gone a long way to eliminate waterhemp in that seed bank. Let’s switch gears to giant ragweed. A lot fewer seeds, in contrast to a giant ragweed plant, might have a couple hundred to a few thousand seeds on a mature plant, much bigger seeds. Oftentimes, it’s about the size of soybeans.

You get into that soybean field with giant ragweed. Your grain tank’s got as much giant ragweed as those soybeans. Waterhemp can have up to a million seeds per plant, but they’re all tiny. Giant ragweed, you can get that to germinate down 2, 3 inches and it can last for as long as decades in the soil. Doubleleaf is a great example, 50, 60, 70 years, you can see areas where they’re digging basements at what used to be cornfields. The first weed that pops up on that dirt pile, doubleleaf, is at least a foot or two. There’s a big difference in the way the plants work. The large-seeded ones oftentimes have a much longer lifecycle on your soil. It can have an influence on how they’re managed, tillage practices, and moisture which can vary which weeds, and you’re getting the bigger flush per year as well.

It is amazing from a biological standpoint, what we learned on weeds, how they thrive and how we can manage them to minimize a lot of pressure. It’s a fun time to understand weeds. There are a lot of corn and soybean products in the marketplace that have herbicide traits bred into them. Specifically, with AgriGold in 2022, offering not only the XtendFlex lineup but also the Enlist. Here we have a lot of options from a post-applied standpoint, starting with a lot of questions. We’re evaluating new products. From a chemistry standpoint or even a product selection, what are some recommendations that you would make to growers so they can make good educated decisions?

The first thing I always recommend is to start cleaning regardless. In terms of XtenFlex and Enlist soybeans, with both of them, we got the option to use Roundup. They both have the option to use Liberty or Glufosinate. Where they differ is that the growth regulator that each one offers is different. One is dicamba, one is 2,4-D. These technologies have been developed because of the challenges of weed resistance. If we go out there and expect to be able to spray any of those three herbicides across a broad acreage but have done a poor job from the get-go, we’re going to break this technology as fast as Roundup was 10, 15 years ago. Regardless of whichever one you’re planting, my recommendation is to start clean. Regardless of whether it’s tillage or a strong burned out upfront possibly using one of those growth regulators since we’ve now eliminated that plant back restriction we had on beans for both dicamba and 2,4-D, depending on which trade system you’re using.

If you’re going to use either one post, dicamba or 2,4-D, both are good herbicides. Slightly different spectrum and what weed they can control. Generally, we’ll get our problem weed that we’re going after because Roundup doesn’t kill ragweed, waterhemps or marestail. Neither 2,4-D nor dicamba ever was as good as Roundup on many of these weeds and neither one does grass. If we think we’re going to be able to go out there with silver bullet number two, with dicamba or 2,4-D, neither one is that. Even though we’ve got a couple more tools available now with Enlist and Xtend, we need to have the same mentality we had years ago before either one existed, and trying to do our best to start clean and stay clean. Simply having a couple more tools early in the season or mid–season with a post-application for either one of them.

I can remember back to my retail days in a burned down no-till situation, 2,4-D was left out of the tank because of planning, restrictions or cost. We relied on glyphosate which did a great job out there. Two or three weeks later, you can start seeing these green mares tails start to pop up. Once that sucker takes off and go, it is a challenge to get it throughout the season. To me, even though we’ve got these great technologies post supply, we’ve got to get aggressive on the front side to make sure these weeds aren’t growing aggressively. Putting on more growing points just makes it much more challenging to manage and kill.

That’s a huge challenge for marestail, waterhemp and ragweed. Growing points is something interesting that I’ve seen. It can happen with Roundup and with the growth regulators, dicamba or 2,4-D. It can have with Liberty. I’ve seen it before, where you do a great Liberty application. Let’s say an 8-inch tall giant ragweed. A little taller than it should be but let’s be real, that’s a very common size that people are out there getting applications done. It can burn it down almost to the ground, doesn’t quite kill it, then all of a sudden that giant ragweed comes back with 2 or 3 stems at the ground. All of a sudden, instead of having single-stemmed giant ragweed, we’ve got three growing points that we’re now trying to kill and get back to the ground. That can happen with any of these technologies.

Having a good start and trying to get these weeds when they are pop–can high. That’s my rule of thumb. If it’s taller than a pop can, it’s getting too big. I’ll steal a quote from Brian Young, one of the professors I had at Purdue, “Give weeds the finger, if weeds are longer than your pointer finger, those weeds are getting too big.” That’s about 3 inches for most people, three knuckles. That’s the size of weeds we got to be targeting with any of these herbicides, regardless of the fact that we got a pretty good treat offering for herbicide resistance on our beans now.

It’s going to be an exciting year moving forward to evaluate both these platforms and be able to offer to growers and to make some good recommendations off of it. We’re looking forward to growers having another option out there to control weeds across the larger geography. We get situations where there are sensitive crops, there are folks who farmed your subdivisions. We need that flexibility to where we can control these weeds and still shoot for optimum yields, specifically in soybean. The last topic I want to talk about with you, you’ve got some growers up in your neck of the woods that are exploring some nontraditional way of growing wheat and soybeans by intercropping. Can you tell us about this process?

To reference back to my short growing season here, we’re in the part of the world where wheat is still planted crop, particularly in the dairy regions because it’s oftentimes spread manure out there. In general, we’ve got soils that can grow good wheat but oftentimes aren’t an economic bang-up crop. It’s good for crop rotation, breaking disease cycles and weed cycles. A lot of people don’t think they can’t justify doing it, even though they may like to.

We’re also too far north to dependably double-crop, I’d say you get north of I-70. It’s not nearly as common as double-crop bean after the wheat. You get north of I-80, it’s pretty much unheard of. My entire part of the world is north of I-80 here, but there are still people that want to try to grow good wheat and would still like to not give up the rest of summer for a cash crop. A lot of people are trying and some people succeed. They’ll plant the wheat in, usually a 30-inch row or 30-inch twin row. You can plant 30-inch beans between those rows. It takes a year that isn’t droughty to have it be successful.

What they do is they harvest that wheat early to mid-July. It’s the typical harvest timing. You also got your equipment set up with the right type of harvest head and tire spacing, etc. You can go in and clip the wheat head, not the straw as well, and do a very minimal amount of damage to those soybean rows that are also out there. You can grow a wheat crop as well as a bean crop on the same field as long as you get that wheat planted in the fall, then get your beans planted on time in the spring. It takes a little bit of fortune, a little bit of planning and a little bit of experience, but some people are doing it with success.

It’s awesome to see that because from the weed control side, the wheat does such a good job of competing. It gives us a few different options from the wheat herbicide side of things that we can break up some weed cycles even while still inter–cropping those beans in there. The two crops are so competitive with each other for the early season time that they snuff out any weeds. If we get a good growing season after the week comes off and get adequate rain, the soybeans and how elastic they are with their stress response, the soybeans can still be awfully good.

It’s not a guarantee every year. Some years work better than others. I’m far from experienced in it. I’ve talked with people. I’ve dabbled in it myself on our little bit of acreage we’ve got. It’s interesting enough that it’s fun to talk about it and neat to see some of the innovation on that. It’s trying to extend our growing season. I see it as cheating in a wheat crop. You can have a corn bean rotation and if you can sneak in a wheat crop that does pretty well, 3 out of 5 or 4 out of 5 years, it makes it worth it. It does a couple of soil health or erosion side of things. We’ve got a winter holding this soil down, some are more sloping fields if it can be pulled off. A square sloping field works out great. It’s pretty cool to see people trying to maximize our short growing season by running a little relay race between some crops.

This concept is one of the coolest things I’ve heard of and seen on Twitter. I follow some of your growers on how they do it. Outside of the logistical standpoint of trying to plant a crop or harvest a crop when the crop is growing, are there any challenges that go along with trying to grow these two crops together?

In my opinion, it would be the nitrogen side for the wheat. How do you adequately feed your wheat with nitrogen, not discourage the beans from modulating and growing on that? That’s one question that I have a great answer for but it’s something that they consider. Also, how aggressive you get with trying to grow your wheat such that it lodges, goes down, etc. It’s very hard to harvest a wheat crop amidst a growing green and bean crop. If the wheat lodges and smothers your beans then you’ve got iffy wheat and no beans. That’s a great pretty tough situation.

There’s a little bit of an art as much as the science. I’ve dabbled in it a little myself. Hopefully, after some time I’ll be able to say a little more specifics as to what I think is successful beyond just the conversations I’ve had with those that have done it. It takes some forethought planning. If you can get 2/3 to 3/4 of a typical wheat crop and every bit of 2/3 to 3/4 quarters of a typical bean crop, that adds up to more than one, and oftentimes makes it a good decision to have done it. If we’re looking for 70 to 90 bushel of wheat, which is pretty doable up here if you can be happy with that 65 to 70-bushel wheat maybe, and then instead of pulling off 60 to 65 bushel of beans, they run 45 to 55 maybe up to 60. You can make that work, but how to do it, how to get that nitrogen to the wheat, how to keep your modern harvest equipment off the rows, how to do it on a big enough scale to make it worth it? Those are all very good questions. Some have, many are trying, myself being one of them.

Every time you get a good idea you take a big leap forward and when the challenges come in, it feels like you take three steps backward. As long as there are opportunities to increase revenue and yields, growers out there will find a way to make a system like this work in their geography. I appreciate you bringing that to our light. As we wrap down and wind down this episode, is there any parting words you’d like to share with everybody?

I’m pretty excited at what we’re looking at so far. I think we’re finally set up for a pretty good year. Here in Wisconsin, we thus far are not fighting the many challenges of 2018 and 2019 and to a smaller extent 2020. I’m looking forward to 2021. I think there’s a lot of optimism out there across the countryside. Many people are going around, there are still challenges, prices are up, but it seems like everything else is up as well. Might be awash in many situations there. In general, I think many people are looking forward to the season we’re starting with so far. I’ve told a lot of people, let’s use the lessons learned from a couple of tough years and let’s apply that to what’s looking like a good setup. Try and do the best job we can, maybe a shoestring type mentality we have in the last couple of years and make a good goal of it and get it to take an opportunity to do well here. That’s something that’s been fun to talk about. People are buying into that concept quite a bit. I’m looking forward to it. I’m excited about what we got going on.

I would like to thank you for your time and insight on the value of splitting nitrogen and considering adding sulfur in the areas that we need to because we’re no longer getting the free nutrients from rainfall. I liked how you’re challenging yourself from an agronomic standpoint of projects and looking at different ways to validate good stands that will eventually lead to higher yields. You gave us great insight and deeper dive into understanding modes of action, sites of action, and understanding how to evaluate products and pre-mixed products that are going on in our field specifically with Group 15s. Making sure that we’re getting space in there for a corn bean rotation. At the end of the day, bringing innovations of intercropping soybean and wheat into a scenario that allows growers in your part of the world to tap into more profit. Thanks for tuning in. We’ll talk to you next time.

Important Links:

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Yield Masters Podcast Community today: